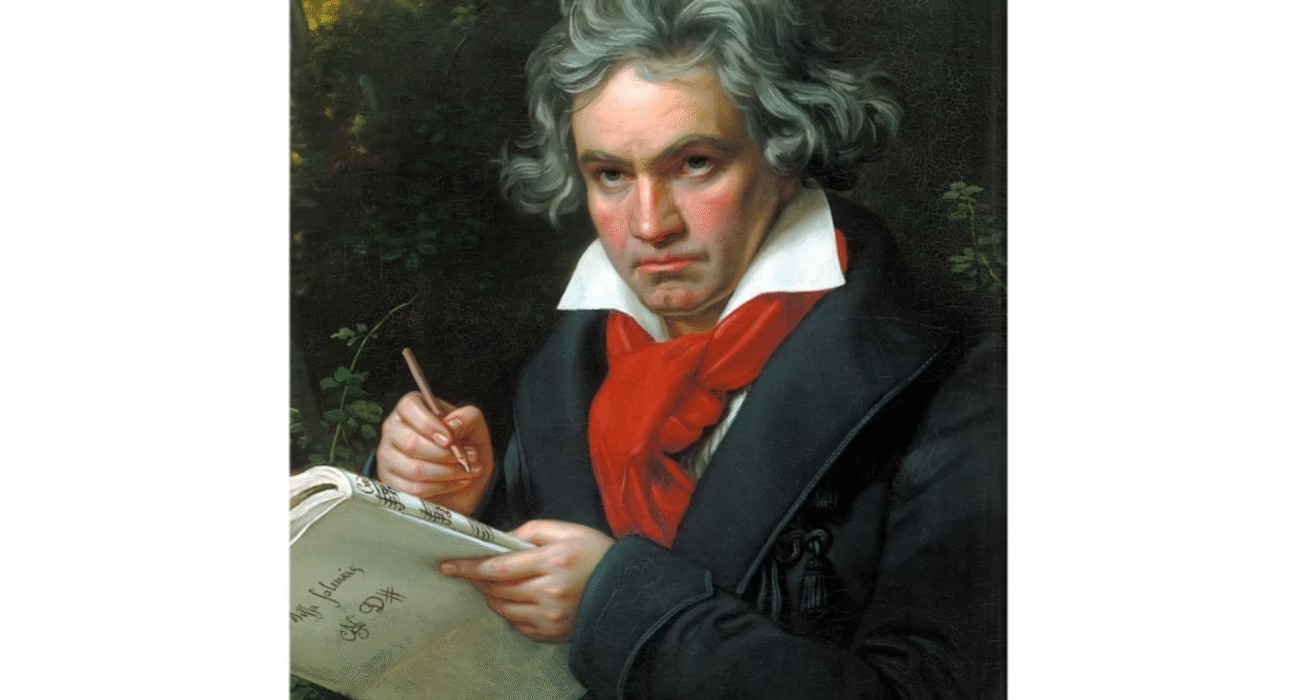

A portrait of Beethoven. Here, he is painted holding the score for “Missa Solemnis.” Public Domain

Beethoven’s music inspired many writers, who honored the great composer in their works.

The relationship of music and literature is deep. Operas were often adapted from works of fiction, especially dramas and epic poems. Literature, too, has often taken inspiration from music in every aspect from theme to structure.

Among composers, Beethoven probably takes the top honor for being most frequently referred to by great authors. In overcoming his deafness to transcend the material world through sound, he is a symbol of transcendence. Below are some of the ways that writers have worked the composer into their stories (and one way the composer was himself inspired in turn).

‘Ode to Joy’

Before getting to how Beethoven influenced writers, we should mention the most famous example of a writer who influenced Beethoven.

Friedrich Schiller is one of Germany’s great poets. In the English-speaking world, he is probably best-known for his poem “Ode to Joy,” which Beethoven incorporated into the climax of his Ninth Symphony. In William F. Wertz’s classic translation, the first stanza reads:

Joy, thou beauteous godly lightning,

Daughter of Elysium,

Fire drunken we are ent’ring

Heavenly, thy holy home!

Thy enchantments bind together,

What did custom stern divide,

Every man becomes a brother,

Where thy gentle wings abide.

Schiller’s poem is pretty long, and Beethoven only incorporated about half of it. He cut out some hedonistic parts that reference kissing and wine. He also reordered it to move smoothly from the earthly to the heavenly sphere, ending with a description of the Creator beyond the stars.

Because of these changes, some think Beethoven’s adaptation is better than Schiller’s original poem. The contemporary poet Brian Yapko, in his own dramatic verse monologue titled “Ode to Joy,” even ascribes this view to Beethoven himself who reflects on his piece’s first performance:

This much I grasp. The music that I’ve wrought

Has left the words of Schiller much improved.

In melody and harmony I’ve caught

True brotherhood and God, and all I’ve loved.

I could not face the audience for fear!

But when I turned, I saw Vienna cheer!

‘The Kreutzer Sonata’

Leo Tolstoy’s novella “The Kreutzer Sonata” might be the most famous example of a work of literature inspired by a piece of music. The name is taken from Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 9, which he dedicated to the renowned French violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer. In Tolstoy’s story, the sonata becomes an expression of the main character’s jealousy toward his sensuous wife. In the central scene, this man, Pozdnyshev, describes hearing her accompany a violinist on the piano:

“They played Beethoven’s ‘Kreutzer Sonata.’ … A terrible thing is that sonata, especially the presto! And a terrible thing is music in general. … They say that music stirs the soul. Stupidity! A lie!” Pozdnyshev argues that music “makes me forget my real situation. It transports me into a state which is not my own. … I really seem to feel what I do not feel, to understand what I do not understand, to have powers which I cannot have.” He concludes: “In China music is under the control of the State, and that is the way it ought to be.”

Something happens to Pozdnyshev upon hearing his wife play Beethoven, however, despite his radical opinions. As he listened, “the consciousness of this indefinite state filled me with joy,” and the music “transported me into an unknown world.” Although the story has a tragic conclusion, there was temporarily, “no room for jealousy” in Pozdnyshev’s heart.

Several times in the story, Pozdnyshev refers to the opening “presto” movement of Beethoven’s sonata. This innovative section begins with a few notes in the major key before shifting to minor, a reversal of the usual harmonic progression where a work begins in minor and shifts to major. It has been described as “furious“ and full of passionate intensity, much like Pozdnyshev himself.

‘Doctor Faustus’

Nobel prize-winning author Thomas Mann put a new spin on the tale of Faust, the age-old story where a scholar sells his soul to the devil. In his novel “Doctor Faustus,” the main character, Adrian Leverkühn, is a composer who makes an infernal pact to pursue novelties in musical style.

Beethoven features prominently in this book full of musical ideas and references. His Ninth Symphony even plays a crucial symbolic role in Leverkühn’s mental and moral downfall.

In Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s “Faust,” the protagonist finds redemption. His soul is saved at the end, and he ascends to heaven through divine mercy. In Mann’s version, on the contrary, Leverkühn’s pact with the devil leads to madness and death. The ultimate catalyst for this is his final composition, a choral work titled “The Lamentation of Dr. Faustus,” intended to be a sorrowful negation of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.”

In writing his novel, Mann was heavily influenced by modernist music. As such, the book can be read as a cautionary tale of the despair that modern art often causes in its excessive devotion to novelty.

‘Four Quartets’

While T.S. Eliot is most famous for his pessimistic early work “The Waste Land,” his later poem “Four Quartets” is arguably his real masterpiece. In writing this work, Eliot was heavily influenced by his turn to Christianity. He also turned to Beethoven, saying of the composer: “There is a sort of heavenly or at least more than human gaiety about some of his later things. … I should like to get something of that into verse once before I die.”

The result was “Four Quartets,” a long poem with a five-part musical structure that mirrors the five movements of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 15 in A Minor, Op. 132.

The first part, “Burnt Norton,” opens like an allegro movement, with short, mostly unpunctuated lines that move quickly. The verse then transitions to longer, reflective lines corresponding with an adagio tempo:

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

I can only say, there we have been: but I cannot say where.

And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time.

That wonderful line, “the still point of the turning world,” is usually interpreted as symbolizing God’s eternal presence. Though unchanging and existing outside of time, He sustains all motion.

By way of conclusion, we can do little better than to quote from E.M. Forster’s novel “Howard’s End.” In a celebrated section, he describes Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as “the most sublime noise that has ever penetrated into the ear of man,” and that he “brought back the gusts of splendour, the heroism, the youth, the magnificence of life and of death.” This passage could just as well apply to all of the composer’s works.

Original article: https://www.theepochtimes.com/bright/symphonies-and-sentences-beethoven-in-literature-5876936

✉️ Stay Connected — Subscribe for Weekly Updates

Discover timeless stories, practical wisdom, and beautiful culture — delivered straight to your inbox.

*We only share valuable insights — no spam, ever.

Duc

Tháng 10 27, 2025very good article