Linear perspective is a fundamental artistic technique that revolutionized the way we perceive and create visual art. This method of representation allows artists to create the illusion of depth and three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface, bringing scenes to life with a sense of realism and spatial awareness.

The Origins and Evolution of Linear Perspective

Linear perspective emerged during the Renaissance as a groundbreaking artistic innovation. This technique fundamentally changed how artists approached spatial representation in their work, ushering in a new era of realism and depth in visual arts.

Ancient Beginnings and Medieval Misconceptions

In ancient times, artists struggled to accurately depict three-dimensional space on flat surfaces. Egyptian art, for instance, often featured figures and objects arranged in rigid, flat compositions without any sense of depth or perspective. The ancient Greeks and Romans made some progress in creating the illusion of depth, but their understanding of perspective remained limited.

During the Medieval period, artists continued to grapple with spatial representation. Many paintings from this era exhibit a lack of consistent scale and depth, with important figures often depicted larger than their surroundings regardless of their position in space. This approach, known as hierarchical scaling, prioritized symbolic importance over spatial accuracy.

Renaissance Revelation

The breakthrough in linear perspective came during the Italian Renaissance, primarily attributed to the architect and artist Filippo Brunelleschi. In the early 15th century, Brunelleschi conducted experiments in Florence that laid the foundation for a systematic approach to creating the illusion of depth.

Brunelleschi’s insights were further developed and codified by Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise “Della Pittura” (On Painting) in 1435. Alberti described the picture plane as a window through which the artist views the subject, introducing concepts like the vanishing point and horizon line that became central to the practice of linear perspective.

Spread and Refinement

The principles of linear perspective quickly spread throughout Italy and beyond, revolutionizing the art world. Artists like Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, and Leonardo da Vinci embraced and refined these techniques, creating works that astounded viewers with their sense of depth and realism.

As the Renaissance progressed, artists continued to explore and expand upon the principles of linear perspective. They developed techniques for handling multiple vanishing points, foreshortening, and atmospheric perspective, further enhancing the illusion of three-dimensional space in their paintings.

The Impact of Linear Perspective on Art History

The discovery and widespread adoption of linear perspective marked a pivotal moment in art history, influencing not only how art was created but also how it was perceived and understood.

Renaissance Revolution

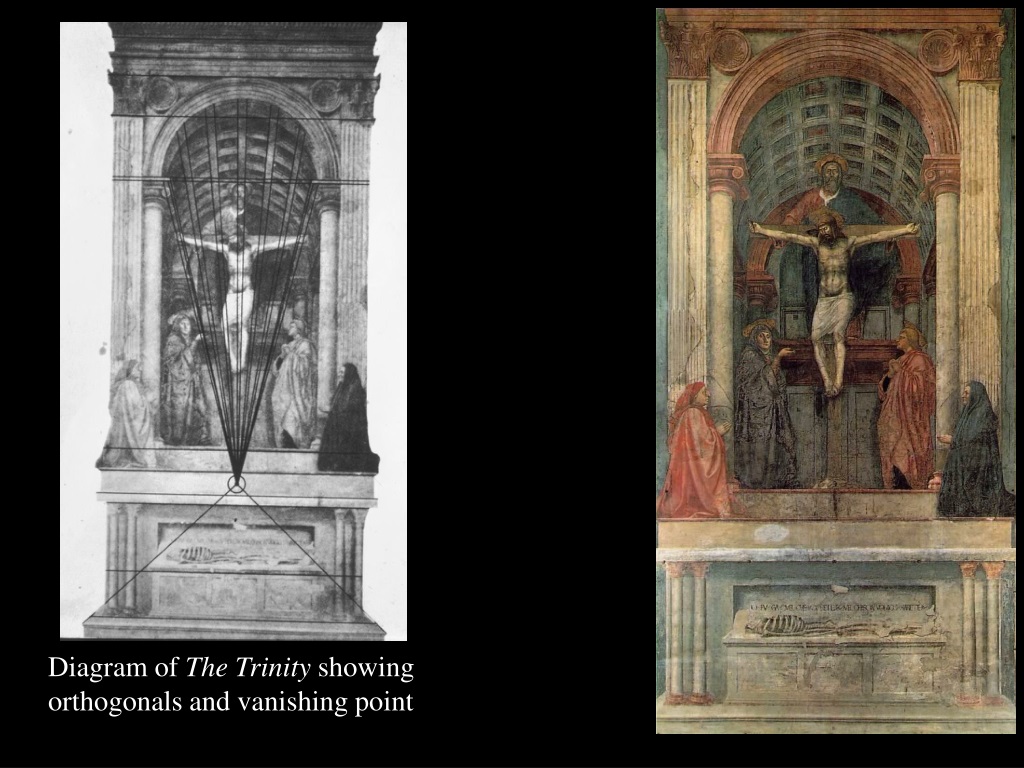

The introduction of linear perspective during the Renaissance was nothing short of revolutionary. It allowed artists to create highly realistic depictions of space, bringing a new level of naturalism to painting and drawing. Works like Masaccio’s “Trinity” fresco in Florence’s Santa Maria Novella church showcased the power of this technique, creating the illusion of a chapel extending beyond the church wall.

This new approach to spatial representation aligned with the Renaissance’s broader intellectual and cultural shifts. It reflected a growing interest in the natural world and scientific observation, mirroring the era’s emphasis on humanism and rational inquiry.

Beyond the Renaissance

While linear perspective reached its initial peak during the Renaissance, its influence extended far beyond this period. Baroque artists like Caravaggio and Rembrandt used perspective techniques to create dramatic, immersive scenes that pulled viewers into their narratives.

In the centuries that followed, perspective continued to play a crucial role in Western art. Even as movements like Impressionism and Cubism challenged traditional representational techniques, they often did so in dialogue with the established principles of perspective.

Global Influence and Cultural Exchange

The development of linear perspective in Europe had far-reaching effects on global art. As European artistic techniques spread through trade and colonization, perspective methods influenced artistic traditions in other parts of the world.

In some cases, this led to fascinating hybrid styles that combined local artistic traditions with European perspective techniques. Japanese ukiyo-e prints, for instance, began incorporating elements of linear perspective in the 18th and 19th centuries, creating a unique blend of Eastern and Western artistic approaches.

The Science Behind the Art

Linear perspective is not just an artistic technique; it’s a mathematical system grounded in optical principles. Understanding the science behind this method helps us appreciate its power and versatility in creating convincing spatial illusions.

The Geometry of Vision

At its core, linear perspective is based on the way our eyes perceive the world around us. As objects recede into the distance, they appear smaller and closer together. This phenomenon is due to the conical nature of our vision – light rays from objects converge as they enter our eyes, creating a predictable pattern of size reduction and convergence.

In a linear perspective drawing or painting, this optical effect is recreated using a set of geometric rules. Parallel lines in the real world are depicted as converging lines on the picture plane, meeting at a vanishing point on the horizon line. This creates a convincing illusion of depth that mirrors our natural visual experience.

The Role of the Vanishing Point

The vanishing point is a crucial element in linear perspective. It represents the point on the horizon where parallel lines appear to converge. In a one-point perspective, all receding parallel lines meet at a single vanishing point. Two-point and three-point perspectives involve multiple vanishing points, allowing for more complex spatial representations.

The placement of the vanishing point(s) significantly affects the viewer’s perception of the scene. A centrally located vanishing point creates a sense of balance and symmetry, while off-center vanishing points can introduce dynamism and tension into the composition.

Measuring and Proportion

Another key aspect of linear perspective is the systematic reduction in size of objects as they recede into the distance. This is achieved through careful measurement and proportion. Artists use techniques like the distance point method to accurately determine the relative sizes of objects at different depths within the pictorial space.

By adhering to these mathematical principles, artists can create scenes that not only look realistic but also maintain internal consistency in terms of scale and spatial relationships.

Mastering the Technique

Learning to effectively use linear perspective requires practice and a solid understanding of its principles. Artists and students of art can benefit from mastering this technique to enhance their ability to create convincing spatial illusions.

Basic Exercises for Beginners

For those new to linear perspective, starting with simple exercises can help build a strong foundation. One common exercise is drawing a row of evenly spaced telephone poles receding into the distance. This helps in understanding how parallel lines converge and how objects diminish in size as they move away from the viewer.

Another useful exercise is drawing a simple room interior using one-point perspective. This allows practitioners to apply perspective principles to a familiar environment, focusing on elements like walls, floors, and furniture to create a sense of depth.

Advanced Techniques and Applications

As artists become more comfortable with basic perspective, they can explore more complex applications. Multi-point perspectives allow for more dynamic compositions and can accurately represent complex architectural spaces or landscapes.

Linear perspective can also be combined with other techniques like atmospheric perspective, which simulates the effect of air and distance on color and detail. This combination can create highly realistic and immersive scenes, particularly useful in landscape painting and architectural rendering.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

While mastering linear perspective, artists often encounter certain challenges. One common mistake is inconsistency in vanishing points, which can lead to a disjointed or unrealistic appearance. Maintaining awareness of the established vanishing points throughout the composition is crucial.

Another pitfall is overreliance on perspective at the expense of artistic expression. While linear perspective is a powerful tool, it should serve the artist’s creative vision rather than constrain it. Many successful artists know when to adhere strictly to perspective rules and when to bend them for artistic effect.

Linear Perspective in the Modern and Contemporary Art World

While linear perspective has been a cornerstone of representational art for centuries, its role and relevance have evolved in the context of modern and contemporary art movements.

Challenging Traditional Perspective

Many modern art movements deliberately challenged or subverted traditional perspective techniques. Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, famously broke with single-point perspective to present multiple viewpoints simultaneously. This approach reflected a new understanding of space and time influenced by developments in science and philosophy.

Abstract art movements further departed from conventional perspective, exploring non-representational forms and spatial relationships. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian created works that eschewed realistic depth in favor of abstract compositions that emphasized color, form, and emotion.

Digital Age and New Perspectives

The advent of digital technology has opened up new possibilities for exploring and manipulating perspective. 3D modeling software allows artists and designers to create complex spatial environments that can be viewed from any angle. This has had a profound impact on fields like architecture, product design, and video game development.

Virtual and augmented reality technologies are pushing the boundaries even further, creating immersive experiences that challenge our traditional understanding of space and perspective. These technologies are not only influencing how art is created but also how it is experienced and interacted with.

Contemporary Reinterpretations

Despite challenges to traditional perspective, many contemporary artists continue to engage with and reinterpret linear perspective in innovative ways. Photorealist painters like Richard Estes use precise perspective techniques to create hyper-realistic urban scenes, while installation artists like James Turrell manipulate light and space to create perceptual experiences that play with our sense of depth and dimension.

Some contemporary artists use perspective as a conceptual tool, exploring themes of perception, reality, and representation. For example, the work of M.C. Escher, while not strictly contemporary, continues to influence artists who use impossible perspectives and optical illusions to challenge viewers’ perceptions.

Conclusion

Linear perspective, from its revolutionary emergence in the Renaissance to its continued relevance in the digital age, has profoundly shaped the way we create and perceive visual art. This technique has not only provided artists with a powerful tool for creating illusions of depth and space but has also influenced our broader cultural understanding of representation and reality.

As we look to the future, linear perspective continues to evolve and adapt. While it may no longer hold the dominant position it once did in Western art, its principles remain fundamental to many forms of visual communication. From traditional painting to virtual reality, the legacy of linear perspective endures, reminding us of art’s power to shape our perception of the world around us.